1894 - Photographing the Flinders Ranges.

Henry Tilbrook retired in 1891 and moved to East Adelaide where he maintained his interest in photography, and in September 1894 he made another trip to the North with Fred Lester. I have included Henry's description of their tedious travelling arrangements so that they can be compared with today’s equivalent mode of travel -- a quick trip north in a four-wheel drive with a small camera loaded with colour film tucked away in a travelling bag.

Henry wrote: ‘In the year 1894, Mr Lester having obtained leave of absence from his official duties as Resident Secretary of the A.M.P. Society at Clare, asked if I would accompany him on a second excursion into the Far North. I was very willing and, of course, accepted. I was now living in Adelaide and all my arrangements with Mr Lester were made by correspondence.

‘This time, although I took my combined hammerless gun and rifle with me, I decided as my main objective to obtain photographic records of the scenes of our explorations. I packed my 8 x 5 camera, with Ross lenses of three kinds – Rapid Symmetrical, a short-focus symmetrical, and a pair of stereoscopic lenses – with an old brand of plates which, unfortunately, did not give the best of pictures. They were not orthographic either, and the "distances" in my negatives on this trip were not as distinct as I afterwards succeeded in obtaining with isochromatic plates and Burchett and Ilford color screens.

‘Wednesday, August 29th, 1894. We had previously made all preparations for our journey and I left Adelaide by train on the morning of the above day. I was to meet my friend Lester at the Farrell's Flat Railway Station. He was there on the platform awaiting me when the train arrived. The train does not stay many seconds there, but he was soon in the carriage with me. Out greetings were warm as we had not seen each other for five years.

‘At Terowie we changed to the narrow gauge, and arrived at Carrieton at dusk. This time we were in a greater fix than on the previous trip in getting to our ultimate destination -- Uroonda. My friend had fixed Monday for our start, but owing to some hitch was not relieved at his office until Tuesday. When Mr Solly arrived with his trap at Carrieton on Monday, instead of getting us he got a telegram informing him we would not arrive until Wednesday night. Naturally he would not drive fifty miles twice, and accordingly wired us to go by coach twenty miles to Glasson’s, where he would meet us with his four-wheeler and convey us the other five miles to his homestead.

‘Arriving at Carrieton with our pile of luggage, which included ammunition, photographic material, provisions, etc., we first had to get to the township, one and three-quarter miles away, across the creek. I got the publican's trap and driver and made this trip three times before all of our belongings were at the public house. It was pitch dark, there being no moon. Soon all our goods were packed on the mail cart -- it was not a coach -- and we made a start. The weather was cold.

‘There were five of us aboard, one being a woman. It was dark above, and dark below, and no part of the track was visible. Occasionally we crossed a dry creek. If we were between the two white posts, all was well. If not, we might be anywhere. We had no lamps. The driver said he could see better without them, and I think he was right. The woman was not a bit nervous.

‘I asked the driver if he had ever got off the track. He said, Yes. One dark night he went astray and drove his two horses over a six-wired fence, but the fence pulled up the trap. He managed to get the horses back, and eventually found the track again. By and by we saw big fires ahead. People who were waiting for their mails had fired some bushes, for the double purpose of warming themselves and guiding the mailman. After a twenty mile drive of three hours’ duration we arrived at Glasson’s. True to his word Mr Solly was there awaiting us, with his trap and pair. It took some time to unload and then reload our impedimenta. Another drive of six miles took us to Uroonda. It was now past 10 o’clock. Mr Solly’s house had grown from two rooms to four during our five years' absence, and his little-girl children had increased in numbers.

‘August 30th, 1894. In the morning I went to the nearest high ground and had a look northward again into the Never-Never-Land which we were bound for. The big ranges loomed up like the Blue Alsatian Mountains, and they held a fascinating charm for me. Uroonda itself is surrounded by low elevations, and was anything but interesting, there being nothing either grand or striking to arrest the eye.

’Tis distance lends enchantment to the view,

And robes the mountain in its azure blue.

The transportation arrangements Mr Solly had made for them did not live up to their expectations. ‘To our consternation Mr Solly gave us only one horse! He had no harness to spare for two -- so he said. We were pretty wroth over it. Our agreement was for a pair and trap. It was the same old four-wheeled express wagonette (as on 1889 trip), but with four new wheels, whereat we were pleased. But upon examination I found there was no brake on the turn-out. And we were going to travel for three weeks through a land without roads, nothing but tracks, and also in places with no tracks at all, and down long slopes miles in length. And down precipitous banks of creeks, some of them dangerous to negotiate even with a brake.

‘I myself was vastly annoyed. For the first time I spoke plainly to him, and pointed out the folly of giving us a trap in that condition. Lester and I consulted and, finding that we would either have to give up our trip altogether or take what was offered us, we decided upon the latter course.

‘It appears, black as things looked, there was some excuse for Mr Solly’s action. At the last moment he started to put the brake in thorough order when, to his consternation, it broke altogether. There being no blacksmith nearer than Cradock, and time being short, he took the brake off altogether. We started off with one horse at about 11 am.

‘Having gone a mile or two we found one horse quite unequal to the task, and returned for another one. Our horse wanted company. This time we were determined to have it. Our load was very heavy. The season had been very dry, water was scarce, while feed was entirely absent. We had to load up with chaff, bran, wheat and oats for our horses. Mr Solly galloped about his farm and found another animal for us. Then we harnessed the two, with a pole instead of shafts, the same pole that we had on our first trip. This pole was enormously heavy, and had a tendency to nose itself towards the ground. It greatly distressed the horses owing to its weight and sagging propensities. We were off at last, at 12.30 pm, late, but with a pair of good horses.

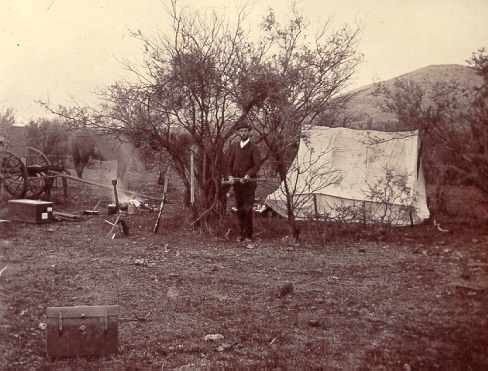

‘Having made a late start, the day was declining as we neared Phillips’s Gap. I had a great job to obtain even a moderately straight ridgepole for our tent out of the very crooked acacia trees. This time we had a splendid tomahawk, one I purchased in town and brought up with me. It was a pleasure to use it, and it made our work of pitching camp much lighter than it was on our first trip into these regions. (Photograph below)

‘Both of us worked with a will and ere darkness set in we were fairly comfortable, with the horses watered and attended to. The water, as ever, was thick yellowish stuff, and we had to use it for our tea. In the night some cattle came around our tent and tried to browse on us. Perhaps they were after our chaff and bran. I lifted up the side of the tent and drove them off. I had to repeat the performance several times during the night and did not get much sleep. While here I was able to fix up a kind of handbrake for our trap.’

The handbrake Henry made was fashioned from a piece of board off a packing case, three inches wide by two feet long. He cut a piece of bent stick from the scrub and with the two nails that were in the board nailed it to the trap so that it rested on one wheel. By leaning on the stick he was able to slow the trap when going down dangerous inclines. If the slope was very steep he had to get out of the trap and walk beside it to lean more heavily on the makeshift brake which survived the full distance of their excursion.

Below: ‘A Camp at Phillips’s Gap, nr. Hawker’ Enlarged section of one half of a stereo pair. Fred Lester in the picture.

‘The morning broke thundery. Big clouds were overhead. Lightning flashed and Jove’s thunder roared, but no rain fell. It was a dry storm. From here we had a fine view of some attractive-shaped hills to the eastward. After taking a stereoscopic and also an ordinary view of our encampment we started on our day’s journey. getting again into the Blinman Travelling Stock Track at the junction of the sparsely but beautifully-gummed Wonaka Creek we proceeded northward. It was now blowing a great gale in our faces. Dust obscured the view and it was a bad day for photography. On the road I took a long range photo of the Kappala Range on our left. The posts of the paddock are showing in it.’

They picked a spot for their camp, but abandoned it when Henry discovered there was a centipede under practically every stone he picked up. They settled on a piece of ground which had a patch of green grass under a large gum tree, but far enough away to escape the danger of falling branches. Henry wrote that ‘rabbits were about in thousands now. Five years previously there wasn’t one in the land!’

|

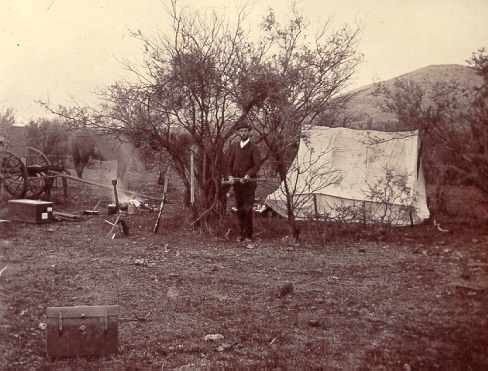

Left: ‘A Gorge. Hookina Creek.’ One half of Henry Tilbrook’s stereo pair. The glass negative appears to have been damaged at the top right corner. |

Despite suffering from what he called influenza, but which he later learned was very severe hayfever, Henry went out hunting and photographing. One evening they returned to camp to find one of their horses had wandered off. It was a serious situation and Henry had to follow her tracks in the twilight, falling over rocks as he went, then after dark used up a box of matches in sticking to her trail. Luckily the horse was found and they were spared what could have been several days of searching for the animal.

Henry took a four-piece panoramic view of Elder Range. ‘The panoramic view of Elder Range I obtained from the subordinate range on the eastern side, eight hundred feet above the separating valley. So the valley shown in the picture may be noted as eight hundred feet beneath the camera. The height I obtained with an aneroid mountain barometer. Elder Range climbs up from that beautiful shrub-studded valley, reef by reef, hill by hill, intil the culminating long range is reached, capped with one hundred feet of bare rock. On the lower hills are bluebush, broom and other bush, pines, and here and there stunted gum.’

Henry spent a lot of time climbing hills and picking his way along rock-strewn watercourses to obtain interesting photographs. ‘It was hard work climbing the ranges to obtain photos, but I persevered. At night I had to change plates, with my head in a ruby-colored bag and a candle outside. Marianne had made me this bag of turkey twill, doubled. It had a little ruby glass window through which came the dull candle-light.

‘This red bag was really a small tent which I placed inside the 8 x 6 calico tent, over the shortened camera stand. With my arms, head and shoulders inside this, and the lower end tied tightly around my waist with strings to keep out all white light, and the candle outside the little ruby glass window, I changed the plates every night. It was a tiresome job, as I was on my knees all the time, and the perspiration rolled off me.

‘The candle through the ruby glass gave me enough non-actinic illumination to enable me to see what I was doing, but much of the work I did by touch. I had to take the exposed plates out of the dark slides, pack them carefully in their proper rotation, label them, as it was absolutely necessary to know each individual plate, as each negative required distinctive treatment with the developer according to exposure and the class of subject. Some required four grains of pyro, some six grains, and others eight grains of pyro to the ounce in the developer. Some wanted the developer diluted with an equal bulk of water; some wanted retarding with bromide of potassium, or metabisulphite more than others.

‘Thus it was that I must know the name of each plate before I developed it. I did no development in the field, but waited until I got home. By my thoroughness and care I did not spoil a single plate.

‘In a portrait studio there is only one developer – namely four grains of pyrogallic acid to each ounce of "A". But out-door view photography is vastly more complicated and difficult. Four grains of pyro with a landscape view nearly all green grass and green foliage would be useless. While, on the other hand, eight grains of pyro on a portrait negative would render it so harsh and hard that the resulting picture would be pure soot and whitewash.

‘All this is technical, but it is necessary to explain why I had to be so careful in changing plates. Then again, dust and fluff, those enemies to good photography, had to be kept off the plates, or terrible ‘pinholes’ would result. I had a plush brush in a cardbord case to keep the dust off with. But it was a very difficult matter even then – for dust is everywhere – it is universal. It will get into every crevice… It was generally a two hours job changing plates – on my knees all the time… Taking the photos involved many miles of walking each day with a heavy load. But the results were worth it, for I have now permanent and almost satisfactory pictures of our visit to those interesting regions.

‘Dear Marianne appreciated and was proud of them, always asking me to show them to her friends and visitors when I arrived home… I wanted Marianne with me to make me happy. I often broached the subject to her, when in Adelaide, of taking trips with me and camping out. But she would not budge!

‘September 6th., 1894. This proved an eventful day. I was engaged all the morning up at the big (Wilpena) range taking photographic views. We could not stay here another night, there being no water for our horses, and our own small supply would run out by midday. Lester took his rifle, intent upon game. I had to climb precipices, rocks and hills, with both my hands full of baggage, a camera over one shoulder, a lens case over the other, for I had to carry four lenses, and a heavy stand. It was hard work! I ascended the seven hundred foot slope in that manner till I reached the base of the cliffs. While engaged in exposing my last plates on the peaks at the side of Rawnsley’s Bluff I was wondering where my mate was.’

Henry found his mate, Lester, but later lost him again and spent many anxious hours waiting for him to turn up at the camp. He fired his gun, hoping to hear an answering shot. He made a large, smoking fire with the aid of green brushwood, but saw no answering signal anywhere. He eventually heard a distant whistle, and replied, and by whistling to each other Lester was guided back to camp. They packed up and reached Wilpena head station that night.

Travelling on they came to Appieallana Water and Ruins where they met two men. One was Captain Stevens, a Cornish miner who was testing the Appieallana copper mine which had been lying idle since 1860 or 1861. The other man was a young Welshman, William Davies, who later became captain of the Paringa Mine and in 1909 was appointed Track Engineer of the Adelaide and Suburban Municipal Electric Tramways.

They set up camp with one end of the ridgepole of their tent fixed into the crumbling wall of one of the ruins. It rained heavily in the night and water spattered in on them through the thin calico covering. At the height of the storm the tent was shaking violently and eventually the ridgepole came out of the wall and the tent collapsed on top of them.

The next day Henry was out taking photographs of The Devil’s Creek, about five miles north of their camp. ‘I took a photo of the high cliff which I had climbed in 1865, while my horse was hobbled in the creek below, and from which I could not descend again except by going clean over the top and coming down another way. It rained all day! I was wet through! My camera was wet through! My waterproof canvas camera bag was wet through! My boots were wet through! And I had a real good time!

‘My boots were giving me trouble. I was afraid that at every step the suction of the mud would draw off the soles. Notwithstanding this I took photo after photo till all my plates were exposed, and I had not one left. Then a minor catastrophe happened. I had just taken a view when, in protecting the lenses -- a pair of stereoscopic ones -- from the rain, my foot slipped from the tapering point of a slimy rock while I was crossing a pool, and I fell on my camera and crushed it! The bottom of the camera was torn completely out.

‘I took out my penknife and tried to mend the camera. But for the remainder of that trip in the Far North my camera wobbled when the wind blew. And when doesn’t it blow when one is out with a camera? Never did I regret the absence of a small screwdriver from my kit as I did then.’

It was dark when Henry returned to the camp, where he found everything had been saturated by the pouring rain. He could not change into dry clothes because there weren’t any, and he did not have a dry rug to sleep in. Because he could not change the plates in his dark slides that night he was not able to take any photographs the following day. The two miners were stranded there without any means of transport and asked if they could get a ride to Hawker with Henry and Fred Lester, who agreed, on the condition the miners left most of their property behind and walked beside the trap. The party of four set out for Wilpena, three of them walking while one had a turn at the reins.

Henry took some photographs at Wilpena with his now very shaky camera which sat on the stand without a screw to hold it in place. ‘That night I changed my last set of plates, keeping my head in the ruby bag till the perspiration rolled off me. Taking photos with dry plates and dark slides is no joke when camping out.’

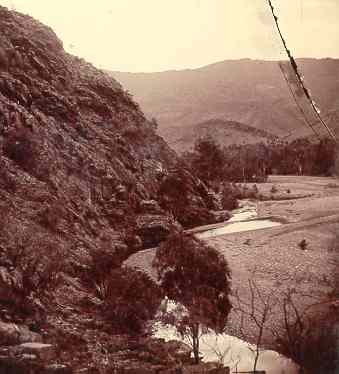

Below: ‘A Camp on the Upper Hookina Creek, near Rawnsley’s Bluff, about 300 miles North of Adelaide and about 10 S. of Wilpena. Taken in Sept. ’94.’ Enlarged section of one half of a stereo pair. Left to right - Fred Lester, William Davies, Captain Stephens.

‘September 12th, 1894. I took two photos of the camp -- one showing the Wilpena Range (Photograph below) at the back, with the euro and rock wallaby skins pegged out on the ground to dry, and the other a stereoscopic view, with a background of trees growing in, and shrubs growing near, the main creek.’ Henry and Stephens came across a very large ochre quarry which had been used by the aborigines.‘I took six views of the scenery here, but unfortunately had not a plate left for the Quarry.’

Below: Flinders Ranges 12 September 1894, from Henry Tilbrook’s postcard called "A camp at Rawnsley’s Bluff". On the left is Captain Stephens, a Cornish miner, Fred Lester at centre, William Davies on the right, and euro and wallaby skins pegged out in foreground.

They travelled on, passing Hawker, and eventually reached Mr Solly’s farm, where they paid him three pounds for the use of his horses and conveyance, and one pound for driving them to the railway station at Carrieton. On the train they met Sydney Kidman, the Cattle King. ‘He caused us much amusement by his loud way of talking, and by the frank manner in which he discussed his own cattle transactions. I at first thought he was what is called in colonial parlance a "skiter". But I soon found he was something superior to that. He did not believe in hiding his light under a bushel. In reality he was one of the best hearted men I have had the peasure of conversing with.

‘In physique, that year, he somewhat resembled a dried up Egyptian mummy -- dark, thin, tough, wiry. Above middle height, tall, in fact. His constitution seemed so sound that I had an idea he would live forever! He, at that time, had not enough flesh on his body for any disease to catch hold of. In the train he spread out his correspondence and his cheques all over the cushioned seats. He talked so loudly with a nasal twang that I could hardly keep from laughing. He was a man of character all right! At last, after an especially loud blast from his trumpet I burst out in spite of myself, but I managed to poke my head out of a window just in time to prevent his noticing my rudeness.’

Henry arrived at Adelaide Railway Station where he writes, ‘my beautiful Marianne welcomed me with a smiling, happy face, and a kiss from her soft, tender lips. How pleased she was at my return! She told me she had been very nervous during my long absence. Captain Stephens died a few years after this and was buried in the Payneham cemetery. I gave them all copies of my photographs, all of which turned out fairly well, considering the dry plates I had.’

|

Left: Flinders Ranges 1894. Henry Tilbrook wrote on the front of this postcard "A creek at the base of Mount Sunderland showing the Sliding Rock formation. Ooraparinna run." |

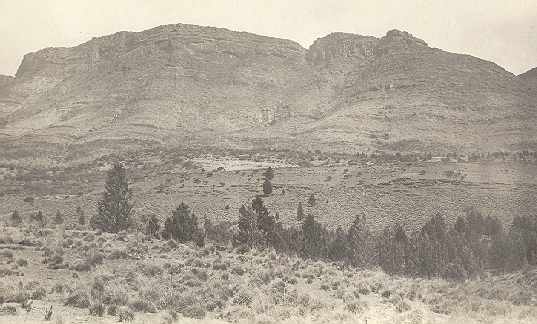

Below: ‘Wilpena Range, Far North, showing spinifex in foreground, and cypress pines in the hollow and at foot of Range.’ From a 14 x 9 inch enlargement in one of Henry Tilbrook’s albums.

END.