The Calotype |

| The earliest known photographs of

South Australia are four calotypes made by an unknown photographer and which are now in

the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh. The calotype was a paper print made

from a paper negative, and because the base material of the negative contained fibres the

resulting prints have a somewhat grainy appearance. The two calotypes reproduced

below are of North Parade, Port Adelaide, as it was c1850-52, and in spite of their grainy

appearance some useful detail is visible in prints copied from the originals. Only a

portion of each calotype has been reproduced to exclude large areas that are lacking in

detail. The four buildings on the right have been identified by the writing on their signs, and are listed below so that the text is immediately above the photograph. Further down North Parade three two-storey buildings can be seen, the first still under construction, the next with no verandah but three arched windows on the top floor, and past that is a building with a balcony-verandah. This group of three two-storey buildings can be seen behind the masts of the ships on the left side of the second calotype which was taken from the other side of the river. Counting from the extreme right the four indentified buildings are : |

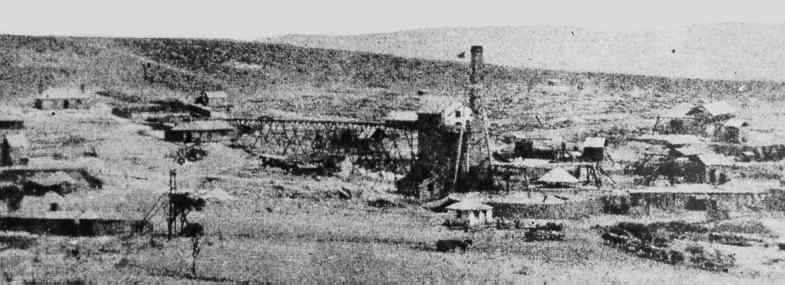

| The other two photographs in the Scottish collection are of the Burra

mine, one of them too faded for reproduction. It was these calotypes of the mine which

allowed fairly accurate dating of the set of four. The calotype below shows Roach’s engine-house which contained the first pumping engine at the mine.

It was named after Captain Henry Roach, the general superintendent of the mine. The engine was ordered in 1847 and arrived on the brig Oak in January 1849. By the end of February about 40 bullock drays had carted the steam engine and pumping machinery to Burra, and on 20 October 1849 about 1,500 people watched the engine start work for the first time. A report of the occasion said it was set to work ‘in gallant style amid the deafening cheers of the assembled multitude. The stonework is of amazing thickness, and about 80 feet in height. The engine is estimated at 85 horse-power and throws up 123 gallons of water per minute, thus effectively revealing the hidden treasures of the mine.’ A much larger 250 horse-power engine was brought into use in September 1852 and Roach’s engine-house was pulled down in 1853. |

| Although some South Australian

photographers advertised their willingness to take photographs by the calotype process,

few calotypes would have been taken as the process was rendered obsolete by the vastly

superior wet-plate system in the early 1850s. However, Benjamin Herschel Babbage did

choose the paper negative process for use on his expedition to the North in 1858. Babbage led an expedition in search of gold both in and north of the Flinders Ranges in 1856, and in 1857 he was selected to lead another expedition to explore the country between Lake Torrens and Lake Gairdner. His plans provided a means for coping with every difficulty he thought might arise. To ensure a sufficient supply of water he had a boring apparatus and pump, four stills for distilling salty water, eight pounds of filtering paper, and a special tank cart which could carry more than 1,100 gallons of water. Details of his plans were outlined in South Australian Parliamentary Paper No. 25, 1858, including his plans for taking photographs on the expedition. In his letter to the Commissioner of Crown Lands, dated 8 December 1857, Babbage wrote: ‘I should take a photographic apparatus to bring back faithful representations of the country traversed by the expedition, and pictures of any rare animals, birds, or vegetable productions that might be met with.’ Also published was a paper Babbage read before the Philosophical Society on 2 February 1858 in which he said that should photography fail, then sketches would have to do: ‘My collector is also somewhat of an artist, as is the case with another of my party, likewise a German. Thus, should the intense heat of the interior prevent my photographical preparations from acting, the sketch-books of myself and my comrades may yet bring back some valuable reminicences of the country. I take with me a camera, which I have constructed expressly for this excursion, so arranged as to avoid the necessity of taking any frames or slides for the paper; and a stock of paper iodized beforehand, in order as to leave as little as possible to be done when upon the journey, and to save the weight and risk of extra chemicals. To avoid as much as possible chances of failure, I have, after many trials, decided upon iodizing my paper with nine different preparations, in the hope that should the heat prevent one preparation from giving satisfactory results, another may be found to succeed. I have been experimenting upon this subject for some months past with a view to the present expedition, and have found that the great heat makes it much more difficult to obtain good paper photographs here than it is in England. One of the difficulties I have had to contend with is the necessity of getting such a preparation as will enable the paper to be kept in a sensitive state for some days notwithstanding exposure to great heat; as it would be out of the question in bush travelling to prepare each morning the paper required for the day’s work. I cannot expect, under these circumstances, to bring back photographs possessing any great artistic merits; but I hope at least to obtain such faithful views as may give a true idea of the nature of the country traversed by the expedition.’ From Babbage’s description it can be seen that he was not taking a cumbersome wet-plate apparatus with him, which required heavy, but fragile, glass plates for negatives, delicate coating and sensitising equipment, some form of portable dark tent, and a supply of clean water for processing. Instead he was hoping to produce paper negatives by using Fox Talbot’s calotype process. The expedition left Port Augusta on 1 March 1858, and several months later Babbage met two exhausted men who had lost their companion, Coulthard. He went in search of the missing man, and on 16 June found Coulthard’s remains under a tree, with a canteen beside him on which he had scratched his dying message. The inscription on the canteen was later photographed in Adelaide by Townsend Duryea Babbage’s expedition was making such slow progress he was eventually replaced and recalled to Adelaide, and it seems that any attempts at photography he may have made along the way were a failure. End. |